Children & Resistance Training - Part 3

Fact or Fallacy: Children should not train with weights. Is resistance training safe to use with children and adolescents?? There are a few questions to be answered in this debate, which are:

- Is resistance training safe to use with children and adolescents?

- Do they need it?

- What are the benefits?

This first article considers safety, and the second article considers whether they need it. This article looks at the benefits of resistance training and an example program.

What benefits can be expected?

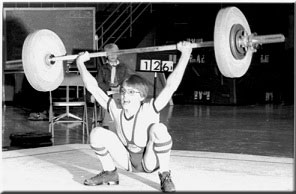

Contrary to the traditional belief that strength and plyometric training are dangerous for children, it is now suggested that such training can be a safe and productive activity.

Convoy et al. (1993)[1] and Virvidakis et al. (1990)[2] found that the bone mineral content of junior Olympic weightlifters was greater than those who do not lift. Fleck & Kraemer (2005)[3] indicate that the bone density peak in boys is between 13 & 15 years & therefore, resistance (strength) training may be essential during these times.

Peer-reviewed research indicates that strength training may be beneficial to young athletes through:

- The prevention of injuries

- Improved body composition

- Improved sports performance due to increased strength, power, and muscular endurance

Kraemer et al. (1989)[4], Ozmun et al. (1994)[5], and Ramsay et al. (1990)[6] show the benefits of resistance training in terms of strength gain and injury prevention. Proper resistance training can enhance strength in preadolescents without concomitant muscle hypertrophy. Such gains in strength can be attributed to neuromuscular "learning." Training increases the number of motor neurons that will fire with each muscle contraction.

Are they ready for it?

Faigenbaum (2002)[6] from the University of Massachusetts in Boston, who is perhaps the most prolific researcher in this area, stated:

"Although there is no minimum age requirement for participation in a youth resistance-training program, all participants should have the emotional maturity to accept and follow direction and genuinely appreciate the potential benefits and risks associated with youth strength training."

What does youth strength training look like?

So, what should the early-stage program look like if you accept that the work needs to be done? Here is a beginner's program taken from the ASCA position statement:

- Basic warm-up (5-minute jog or cycle, etc., plus 2-3 minutes of dynamic stretching).

- Step-ups (both left and right legs) (quadriceps, hamstrings, and gluteal muscles) - 20 to 30 cm step or chair.

- Push-ups (pectorals, deltoid, and triceps brachii muscles) - off knees initially progressing onto toes as strength increases.

- Star jumps (quadriceps, adductors, gluteal muscles).

- Abdominal crunches (abdominals and hip flexors) - as strength increases, progress towards bent-legged sit-ups.

- Chair dips (triceps brachii muscle) - initially, have legs close to the chair and use the legs and arms to raise the body. As strength increases progressively, move your legs further away from the chair.

- 90-degree wall sit (quadriceps and gluteal muscles).

- Reverse back extensions (lower back, gluteal, and hamstring muscles) - lying face down with torso over a table or bench and lifting legs to the level of the hips. Hold the top position for 1-2 seconds and repeat.

- Hover (abdominal, hip flexor, and lower back muscles) - initially off knees, progressing to toes.

- Cool down and stretch - (5 minutes of jogging or cycling, etc., and 5 minutes of stretching)

Progression:

Start at stage 1 when the athlete progresses comfortably and achieves the circuit to the next stage.

- Stage 1: Perform 20 seconds of each exercise for as many controlled repetitions as possible, followed by 40 seconds of rest, and then move on to the next exercise. Perform 1 circuit - total workout time approximately 25 minutes (including warm-up and cool-down).

- Stage 2: Perform 30 seconds of each exercise for as many controlled repetitions as possible, followed by 40 seconds of rest, and then move on to the next exercise. Perform 1 circuit - total workout time approximately 27 minutes (including warm-up and cool-down).

- Stage 3: Perform the same as stage 2, but repeat the circuit 2 times - total workout time approximately 38 minutes.

- Stage 4: Perform two circuits but increase the exercise time to 40 seconds per exercise with 50 seconds of recovery—the total workout time will be approximately 40 minutes.

- Stage 5: Perform two circuits but increase the exercise time to 50 seconds per exercise with 50 seconds of recovery—the total workout time will be approximately 43 minutes.

- Stage 6: Perform two circuits but increase exercise time to 60 seconds per exercise with 60 seconds recovery - total workout time approximately 47 minutes. At this stage, the athlete can keep the same circuit but try to increase the intensity of some of the exercises. For example, some options include:

- Increase the step height for the step-ups.

- Push-ups off toes rather than knees.

- Progress from crunches to bent-legged sit-ups.

- Chair dips are performed with legs progressively further from the chair.

- Hover off toes rather than off knees.

Although I am not a lover of crunches or push-ups off knees, the progression is sound, and this program will achieve results for the youngsters.

Machines are not the way forward; a good S&C coach working with children and adolescents should incorporate as many bodyweight and free-weight activities as possible.

References

- CONVEY et al. (1993) Medicine & Science in Sport & Exercise, 25

- VIRVIDAKIS et al. (1990) International Journal of Sports Medicine, 11

- FLECK, S. KRAEMER, W. (2005) Strength Training for Young Athletes. London, Human Kinetics, p.24

- KRAEMER, W. J. et al. (1989) Resistance training and youth. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 1, p. 336–350.

- OZMUN, J.C. et al. (1994) Neuromuscular adaptations following prepubescent strength training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 26, p. 510 –514

- RAMSAY, J. A. et al. (1990) Strength training effects in prepubescent boys. Issues and controversies. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 22, p. 605–614

- FAIGENBAUM, A.D. (2002) Resistance training for Adolescent Athletes. Athletic Therapy. November p. 32-35

Page Reference

If you quote information from this page in your work, then the reference for this page is:

- CHAPLIN, B. (2012) Children & Resistance Training - Part 3 [WWW] Available from: https://www.brianmac.co.uk/articles/article114.htm [Accessed

About the Author

Brendan Chaplin is currently Head of Strength and Conditioning at Leeds Metropolitan University. In this role, Brendan oversees all performance programs across the university. He leads the GB Badminton High-performance Program, Yorkshire Jets Superleague netball, Women's FA through the English Institute of Sport, and Rugby League. Brendan is also the regional lead for TASS, where he delivers and coordinates delivery for all funded athletes based at the Leeds Hub site. He also consults with England Golf and works with various athletes, from martial artists to cyclists to children and adolescents. Before his current role, Brendan has worked with many governing bodies and institutions, including British Tennis, Huddersfield Giants, English Institute of Sport, Durham University, and many more.