Goal & Process Motivation

Dr Matt Long and David Lowes spent time with Olympic champion David Hemery CBE, who provided an insight into his winning mentality.

It is October 15, 1968, and in the high altitude of Mexico City, a 24-year-old British athlete wearing number 402 is settled in his blocks out in lane six as he attempts to become Olympic champion over 400m hurdles. Now, 44 years later, we analyse the reflections of David Hemery in his finest hour through recourse to the tool of Reversal Theory.

Reversal Theory

Reversal Theory was proposed almost four decades ago by psychologist Dr Michael Apter [2] and consultant child psychiatrist Dr Kenneth Smith. In 1975, this pairing developed a model of human motivation that articulated two primary and opposite motivational states. The underlying philosophy of this theory rejected conventional psychological wisdom by espousing that individuals are not rigidly fixed in terms of definitive personality 'traits' but may have two fundamental 'states' of mind that can be alternated when triggered.

Telic and Paratelic states

In simplest terms, 'Telic' indicates goal-focused motivation and behaviour, whereas 'Paretelic' is a process-focused motivation and behaviour. For example, a javelin thrower's telic state may exceed 70 metres. It will have been pre-planned and agreed upon with the coach and fit into a wider microcycle of periodised training.

The paratelic behaviour of the same javelin thrower may kick in when this goal fades into the background during a competition. The athlete may be feeling the grip of the javelin in their right palm as their number is called to throw or experiencing the rush of adrenaline as a Diamond League crowd claps rhythmically.

The goal has been momentarily forgotten, and the 'here and now' is everything. In describing how a shift between polar states can be affected, internationally respected coach educator Peter Thompson (2006) offers the analogy of a light switch: "Just as the switch on the wall can be either 'on' or 'off', the two stable positions in all of us are opposites" and can be reversed.

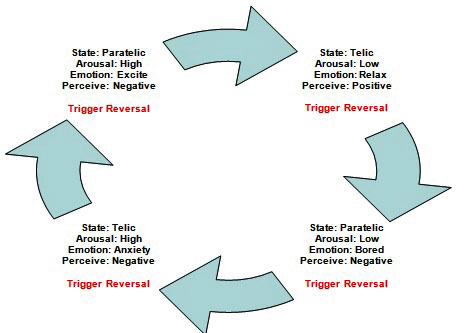

Figure 1: Telic and Paratelic state reversals. Adapted from Apter and Smith (1979)

Pre-race

In the pre-competition mode, Hemery reflects that he was in a 'telic' state of mind with a clear goal focus, "Before the start, the aim was to deliver a world record paced run, and I hoped that would be good enough to win. My goal focus was to avoid losing." It is significant because his doctoral research (published as 'Sporting Excellence' in 1991) involved interviewing 83 elite athletes from 22 sports and 12 nationalities, including golfer Nick Faldo and tennis player Stefan Edberg. While 60% of interviewees aimed to win, the other 40% saw themselves as winners who wanted to avoid losing. David's self-categorisation in the last 40% suggests that retaining his self-image was one way of avoiding the label of 'loser'.

In his autobiography, Another Hurdle (1976), he recalls, "I was practically paralytic with fear in the medical room." Interestingly, he remembers that he and eventual bronze medallist John Sherwood "were able to crack bad jokes in our attempt to relieve the tension." Thompson (2006) articulates how humour is a key trigger in shifting athletes from high-arousal telic states of anxiety towards the high-arousal paratelic state of excitement.

With 50 minutes before the race, Hemery's book recounts a conscious attempt to move away from the goal-focused telic state towards the paratelic while on the warm-up track: "I took off my shoes and jogged around the grass. The dampness under my feet took me back 12 months to when I had been running on the water's edge along the firm sand (of a beach in the USA). I tried to recapture some joyful and enthusiastic thoughts and feelings I had experienced."

The man who would eventually hang up his spikes with a complete set of Olympic medals continues, "The delivery was in a controlled state of fear! The more nervous I was about a race, the faster I ran. I did attempt to take controlled self-management of that state - in the waiting room 20 minutes before the race, reducing my heart rate through slow breathing, focusing on what I could control." According to Hanin (1997) [3], to perform their 'optimum arousal' level, the anxiety of an athlete has to fall within their 'optimum functioning zone.'

Additionally, Hardy and Frazer's Catastrophe Theory (1987)[4] articulates how each athlete will respond differently to competitive anxiety. In contrast to catastrophe theory and optimal arousal theory, Reverse theory allows us to see how Hemery's 'understandable' nerves could be turned into very high arousal and excitement of the kind that is productive for world-class performance.

The Olympic champion's use of controlled breathing indicates the five-breath technique articulated by Karageorghis (2007)[5]. It is most likely that he was a 'paratelic dominant' athlete who was most responsive when the challenges presented the highest level of arousal. He added, "I avoided looking at the opposition or getting drawn into their nervous jogging in that tiny space." This ability not to get sucked into displacement activities that may be detrimental to optimum performance indicates the kind of 'emotional control' described by Brian Mackenzie (1997)[6], which is maintained despite considerable distractions.

The Race

Hemery's account of the 48.12 between the gun and Olympic immortality constantly switches between telic and paratelic states. He launched out in the latter state, recalling, "The primary focus was internal pace judgement and stride pattern/stride length focus." The BBC's animated and emotional broadcaster David Coleman shouts into his microphone, "Hemery is gambling on everything. He is flying down the back straight." A reversal to the telic goal-focused state occurred in those early stages, as Hemery recalls, "I passed one of the pre-race favourites, Ron Whitney, before hurdle three, who was one lane outside of me in lane seven.

I thought he had gone off slowly but would probably be tagging onto my shoulder as I went by." This momentary shift was quickly reverted to the paratelic state with Hemery saying, "I refocused on maintaining my speed and strides through to hurdle six." This was necessary to make an essential technical adjustment to alter the stride pattern from 13 to 15, "which is when I needed to take 12 inches (30cm) off each stride, following a normal take-off and landing.

It also meant accelerating the cadence to avoid losing too much momentum," he added. His book recounts how "I felt as if I were running in slow motion as I saw every inch where I had to place my feet. I was vividly conscious of myself, the red tartan surface, and the hurdles on that final bend." A reversal towards the telic occurred while he was "briefly conscious of passing John Sherwood, who was out in lane eight, but that was more like a pace judgement marker."

Late into the race, Hemery experienced a reversal towards the paratelic due to the rainy conditions that occurred between 4 pm and 6 pm on the day of the final. He recalls, "After hurdle seven, I was again distracted when I heard a foot splash in a puddle, which sounded as if it were only a few feet behind me, to my left." The triggering of this paratelic experience by an environmental cue appears to have instantaneously triggered a reversal back to the telic state, as he vividly remembers, "I intended to win, so it was a blessing as it sent a shock and a shot of adrenaline through me that I hadn't gotten away from the rest of the field."

Once again, anxiety appears to have been an appropriate motivator for the man who would be remembered as one of Britain's best 'Superstars' between 1973 and 1977, with the telic state coming to the fore. He continues, "I did have a potentially negative thought coming into that eighth hurdle, that I wasn't sure that I could hold the pace, and a calm, rational thought came back, 'you have to, this is the Olympic final!' "

Even as the tape loomed, one last reversal from telic to paratelic seems to have occurred, with the looming Olympic gold being momentarily forgotten in favour of more process-motivating thoughts. "As I stepped over the final barrier, on landing, I remembered that Billy Smith, my coach, had written to say, 'Go at the last hurdle as if it's the first in a high hurdles race.' The fact that I had forgotten made me try to change into a sprint, which I didn't feel was a sprint. It was as fast a stride as I could muster to the line."

Coleman screamed into his microphone, "Hemery won that from start to finish. He killed the rest, and he paralysed them!" Over four decades later, a modest Hemery, Vice Chairman of the British Olympic Association, jokes, "I only looked good because the others faded!" He crossed the line almost a second ahead of West German silver medalist Gerhard Hennige and stopped the clock in a world record that catapulted him to the crown of 1968 BBC Sports Personality of the Year.

Conclusions

This article has challenged us to consider the following:

- Rather than having fixed personality traits, athletes can be shifted between two polar mental states: telic and paratelic.

- Elite-level performers like Hemery experience multiple reversals between psychological states before and during intense world-class competition.

- The task of both coach and athlete is to develop an awareness of extrinsic and intrinsic cues that can trigger reversals that positively utilise anxiety and optimise performance.

Article Reference

The information on this page is adapted from Long & Lowes (2012)[1] with the author's permission and Athletics Weekly's kind permission.

References

- LONG, M & LOWES, D. (2012) Mental Hurdles. Athletics Weekly, June 7th, 2012, p. 34-35

- APTER, M. J. (1997) Reversal theory: What is it? The Psychologist, 10 (5)

- HANIN, Y.L. (1997) Emotions and athletic performance: individual zones of optimal functioning. European Year Book of Sports Psychology, 1, p. 29-72

- HARDY, L. and FRAZER, J. (1987) The Inverted U Hypothesis: A catastrophe for sport psychology? British Association of Sports Science, monograph no. 1, NCF, 1987

- KARAGEORGHIS, C. (2007) Competition anxiety needn't get you down. Peak Performance, 243, p. 4-7

- MACKENZIE, B. (1997) Psychology [WWW] Available from: https://www.brianmac.co.uk/psych.htm [Accessed 01/6/2012]

Page Reference

If you quote information from this page in your work, then the reference for this page is:

- LONG, M. and LOWES, D. (2012) Goal & Process Motivation [WWW] Available from: https://www.brianmac.co.uk/articles/article133.htm [Accessed

About the Author

Dr Matt Long is a British Athletics Coach Education Tutor. David Lowes is a former international athlete, Level 4 coach, and Coaching Editor of AW.

David Hemery is the founder of the Charity 21st Century Legacy, an educational program for schools that challenges young people to 'Be the best you can be'!