Minding Your Mental Fitness

David Lowes and Dr Matt Long investigated the mindset of mature elite athletes and the mentality of social athletes.

Training hard is not always enough, although this is the most important aspect. The training mix has to cover all aspects. Suppose the athlete specialises in middle-distance events. In that case, aerobic and anaerobic work will be used in varying proportions with speed, speed endurance, and strength endurance to encourage the development and improvement of the various energy systems.

Elite athletes, in particular, will also add many other aspects to their training regimes, including core work, plyometrics, weights, flexibility, drills, massage, and ice baths - the list can be a long one. Every ingredient becomes almost as important as the next, even if 'running training' remains sacrosanct. Suppose the daily running sessions make up 90% or more of the workload. In that case, even if an ice bath only contributes to 1% or less on the scale of success, that can make a huge difference - perhaps the difference between a successful season and a mediocre one.

Without lingering on what is essential and what is not, a significant area where many athletes and coaches fail to apportion enough time is an individuals' mental fitness at any given time. Changing poor mental states into positive ones that can make huge differences before, during, and after a performance is vital. Being in the right frame of mind is essential to deliver a performance allied with endless hours of steady running and repetitive work on the track for middle-distance athletes.

Many athletes dismiss the importance of psychology in sporting achievement. These are unequivocally the ones who have weak mental states - they are stuck in a rut and cannot see any way out of it! My research over the last three years (2009-present) will give an insight into how important being in the right frame of mind can be and what can be done to get 'in the zone.' The chosen subjects were young and mature, from BMC Residential courses, BMC Grand Prix events, and some elite athletes from Scandinavia, Spain, Kenya, and Ethiopia. The findings will show how positive and negative mental states affect performance and some surprising results regarding differing mindsets.

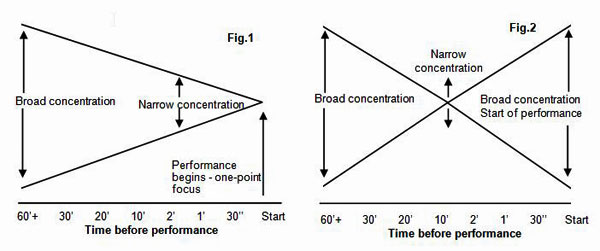

Those who can handle and negate any problems in positivism will have success. The diagram below (Fig.1) shows the ideal model of how the mind should focus on a point (competition) from one hour before the sound of the gun. Those with a successful race will generally relate to this, although exceptions exist. However, those with an unsuccessful result due to poor mental states can almost enact this model in reverse (Fig.2) with an incident or an opponent upsetting their focus. External and internal cues can trigger reversals between telic and paratelic states, some of which enhance optimum performance, and others impede it. Although it is easy to comment that there should be no distractions, unfortunately, this is rarely the case in real-life scenarios.

Athletes with pre-determined (SMART) goals are always more successful than those without. Those with specific goals tend to let distractions affect them less, with an almost indestructible attitude that nothing will stop them in their pursuit of excellence, as seen in the table below, which relates to dedicated runners (goal-oriented) and non-dedicated runners (enjoy the sport, but goals are:

| Mature elite athletes | Social athletes (young and mature) |

| Goal-oriented (specific) | Vague goals (non-race/time-specific) |

| Good focus and concentration levels | Limited focus and poor concentration levels |

| Desire to succeed at the highest level (prepared to give and do as much as it takes) | Hope for some personal success (“see how it goes”), although not top of the list of priorities |

The findings came from a spread of 62 athletes ('mature elite' - national or international standard) and ('social' - club athletes enjoying feeling fit in a social environment without too much thought towards performance), and all remain anonymous. The chosen athletes in the study were asked to give as honest an opinion as possible. Although some information was difficult to disseminate and extrapolate, many of the answers showed that many of their feelings and, thus, performances had not been widely published before. The three most common responses are given below, although many more variations that are not dissimilar were given.

| Time before ‘major' competition | Mindset Mature elite athletes |

Mindset ‘Social' athletes |

| 1 week | (a) Focussed. Positive nerves. I am only nervous if training has not been going to plan (b) Awareness of competition, but concentrating on preparation (c) Irritability. Wishing the competition were ‘here and now' |

(a) No real thought of competition other than it is scheduled (b) Concentrating on the training session at the time (c) Aware of competition, but a “see how it goes” attitude |

| 2 days | (a) Focused and excited (b) Concentration on pre-race preparation (c) Focusing on execution and variables of competition |

(a) Aware of competition but have not given it much thought (b) Aiming to do well, but no specific goal (c) Would like a PB - but not sure how |

| 3 hours | (a) Coinciding with turning up at the venue - positive and relaxed (b) Making everything perfect - hydration, fuel, kit, numbers, checking the time of the competition, and competitors (c) Trying to relax and avoiding any distractions |

(a) Turning up at the venue – no pre-conceived plan - enjoy it (b) Talking to friends with little thought to any preparation (c) Relying on the coach/other athletes to inform them of what and when to start warming up and what to do |

| 1 hour | (a) Pre-warm-up - ensuring a ‘feel-good' (b) Checking timetable for any variance (c) Focus on tasks and conditions and not competitors |

(a) Talking to friends (b) Watching other events (c) Too early to warm up, starting to give some thought to the event |

| 20 minutes | (a) Completion of warm-up (b) Some nervousness (positive thinking) (c) Final talk with coach and tactics |

(a) Warming-up (non-specific) (b) Very nervous and irritable (negatives) (c) Looking for a coach/parent/partner |

| 5 minutes | (a) Stretching plus positive inner thoughts (b) Competition rehearsal (c) Keeping warm and relaxed |

(a) Stretching and talking gibberish (b) Focusing on the uncontrollable (c) Nervously taking the kit off too soon |

| 1 minute | (a) Calm with positive nerves, some agitation (want to go!) (b) Carrying out rituals (adjusting laces, kit) (c) Specific stretches (superstition) |

(a) Nervous and negative thoughts (b) Lack of specific preparation (c) No visualisation of the race - “see how it goes.” |

Start-line |

(a) Focus on the task (b) Concentration on keeping calm (c) Keeping aggression intact |

(a) Extremely nervous (some distress) (b) Scared of opposition (c) All negative thoughts |

| During competition | (a) Keeping relaxed and in the right place (b) Planning when to make tactics most effective (drive to the finish) (c) Focusing on performing to full potential irrespective of others |

(a) Trying to maintain the pace (b) Lack of focus - negative thoughts - slowing down (c) Just trying to finish without any thought of running faster |

Although positive and negative vibes are at opposite ends of the spectrum, they are all related to emotions, and everyone experiences these at varying times and degrees. Indeed, this is normal in accounting for shifts between anxiety and excitement or boredom and relaxation as one constantly reverses telic and paratelic states. Post competition, one of the most common emotions you will see this summer, and hopefully from British athletes, is when they stand proudly on top of the podium in the Olympic stadium. They are delighted, vibrant, and relaxed, yet they are invariably reduced to a blubbering mess when the National Anthem begins! Why is this? Is it because they are so patriotic that it only takes a few bars of "God Save The Queen" to render them to jelly, or is it perhaps all of the sacrificial training? A nomadic lifestyle has come to fruition, and something within is just saying, "You have done it, and it was worth all the proverbial blood, sweat, and tears?"

I am sure many athletes have experienced the phenomenon of the hairs standing up on the back of their necks or a shiver running down their spine when they enter the home straight in front of a rapturous full stadium, be it English Schools or Olympic Games, and that goes for the watching coach and parent too! Sometimes, even a tear is shed as the finishing line approaches, especially when victory or a big PB is about to be recorded at the end of a marathon. Emotions will be fully viewed at the most incredible show on earth this summer. A myriad of sentiments will be apparent to onlookers, including tears of joy and sadness and expressions of delight, anger, and frustration. These emotions need to be controlled during competition, and who cares what an athlete does once they have achieved their goal - the more emotion, the better as far as the TV commentator or spectator is concerned - it is all part of the theatre of sport.

Interestingly, as part of the survey, the mindsets during a competition differed significantly when performing well, instead of poor performance. In terms of running, emotions were also diverse from event to event (800m-Marathon), and the mindsets of some poor performance athletes were admittedly absurd but relevant: thinking about 'socialising', past/future lifestyle events, and considerations of never running again. It is clear evidence of counter-productive 'mental dissociation' in the extreme. However, the three most consistent responses are listed below:

| Event | Good Performance | Poor Performance |

| 800m | (a) Completely focused on position/pace (b) Total focus on execution (high arousal) (c) Unaware of the crowd and aware of athletes in peripheral vision only (intense focus) |

(a) Mindset fluctuating over the final 250m (b) Negative thoughts - too fast - should not be here (total lack of confidence - low arousal) (c) Aware of the crowd, noise, and all athletes |

| 5000m | (a) Focussed on correct pace (execution) (b) Focus on the outcome (performance) (c) Bell causes adrenaline rush (speed up) |

(a) Wanting the race to finish (unhappy) (b) Poor focus (looking only 100m ahead) (c) The sound of the bell is a relief (one lap left) |

| Marathon | (a) Focussed on pace and first 15-18 miles (damage limitation) (b) Lapses in concentration with time to think about training, lifestyle (stress reliever) (c) Increasing and intense focus after 18 miles to offset fatigue and maintain form (focusing no more than two miles ahead) |

(a) Focus on just finishing with no pre-conceived race plan (no backup plan) (b) Mind-wandering with little or no focus on the event (lack of focus and planning) (c) Be aware of crowds, specific people, and landmarks. Aware of every mile and step when tired |

| Cross country | (a) A range of emotions - aggression at the start, relatively relaxed in mid-race, and aggressive on hills and finish (positive) (b) Lapses in concentration and emotions (dependent on spectators/coach cheering) (c) Different mindset over different terrain - mud, uphill, downhill, flat (focus) |

(a) Lack of motivation and concentration, wanting a race to finish as soon as possible (lack of planning) (b) Total disinterest in the race, unable to stop competitors passing (inefficient pacing) (c) Feeling of inadequacy and wondering if all the effort is worth it (low self-esteem) |

Although no research data was taken for field events (this may be the topic of a future article), each discipline has its point of execution where aggression is released. A shot putter will usually get 'fired up' before they enter the circle, and more so when they release the implement. However, a javelin thrower may have more latent aggression, and much control is needed on the run-up before hurling the spear into the stratosphere. Likewise, a long jumper needs a fast run-up to the board before exploding upwards and forward to the sandpit. In contrast, a high jumper needs more restraint to enact the drive into and over the bar, and it is common to see them rehearse their execution before they start their run-up.

Although this article has tried to list some of the mindsets associated with excellent and poor performance, it has not attempted to instruct on how improvements can be made or eradicated. A long list of techniques, including self-talk, affirmations, reframing, pattern-breaking, visualisation, psychosynthesis, swish patterns, and detachment, which can help improve performance significantly, would make an extensive article.

Article Reference

The information on this page is adapted from Long & Lowes (2012)[1] with the authors' permission and Athletics Weekly's kind permission.

References

- LOWES, D. and LONG, M. (2012) Minding Your Business, Athletics Weekly, 21st June, p. 52-53

Page Reference

If you quote information from this page in your work, then the reference for this page is:

- LONG, M. and LOWES, D. (2012) Minding Your Mental Fitness [WWW] Available from: https://www.brianmac.co.uk/articles/article125.htm [Accessed

About the Authors

Dr Matt Long is a British Athletics Coach, Education Tutor, and volunteer endurance coach with Birmingham University Athletics Club. David Lowes is a former international athlete, Level 4 coach, and Coaching Editor of Athletics Weekly.