Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction

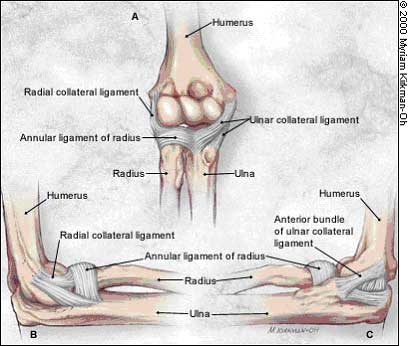

Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction (UCL) is a surgical procedure in which a ligament in the medial elbow is replaced with a tendon from somewhere else in the body. Often, the tendon is taken from the patient's forearm, hamstring, knee, or foot. This procedure is standard among collegiate and professional athletes in several sports, most notably those requiring overhand throwing or striking movements. The surgery was named after Tommy John, a pitcher for the Los Angeles Dodgers, who was the first professional athlete to undergo the operation successfully in 1974. Dr Frank Jobe performed the procedure. After the tendon from the forearm of the opposite elbow or below the knee is harvested, it is then woven in a figure-eight pattern through tunnels drilled in the ulna and humerus that are part of the elbow joint. However, there is a risk of damage to the ulnar nerve when performing this surgery (Purcell et al. 2007)[1]

Process

The probability of a complete recovery after surgery is estimated at 85% to 90%. At Tommy John's operation, Jobe put his chances at 1 in 100. After his surgery in 1974, John spent 18 months rehabilitating his arm, returned for the 1976 season, and pitched in baseball's major leagues until 1989 at age 46.

The procedure takes about an hour today, and complete rehabilitation takes approximately 6-12 months. Athletes who have the surgery may regain their full range of motion after nearly two months and, at that time, start performing weight exercises. For the next four months, athletes can increase their resistance and begin performing exercises emphasising stress on all parts of the arm.

Risk Factors

The ulnar collateral ligament may become stretched, frayed, or torn through the repetitive stress of the overhand throwing motion. The risk of injury to the athlete's UCL in the elbow is considered extremely high as the amount of stress through this structure approaches its ultimate tensile strength during every hard throw (Fleisig 1994)[2].

While many authorities suggest that an individual's style of throwing or the types of throwing motions they use may be the most crucial determinant of the likelihood of sustaining an injury, the results of a 2002 study suggest that the total number of throws is the most significant determinant (Lyman et al. 2002)[3]. There was a weak correlation between throwing mechanics perceived as bad and injury.

Although a large body of evidence suggests mistakes in throwing mechanics increase the likelihood of injury (Whiteley 2007)[4], it seems that the higher risk lies in the total volume of throws. The higher risk lies in the total volume of throws. Research into throwing injuries in young athletes has led to age-based recommendations for throwing limits for young athletes (Lyman et al. 2001)[5].

In younger athletes for whom the growth plate (the medial epicondylar epiphysis) is still present, the "opening up" force inside the elbow during overhand throwing is more likely to fail at this region than at the Ulnar Collateral Ligament. This injury is often termed "Little League Elbow" and does not require reconstructing the Ulnar Collateral Ligament.

Frequency and Misconceptions

Today, UCL surgery is becoming more common in youth between the ages of 10 and 18 due to the increased length of seasons and the increased competition at an early age. In some cases, athletes throw harder after the procedure than before.

As a result, orthopaedic surgeons are reporting that increasing numbers of parents are coming to them and asking the surgeons to perform the procedure on their uninjured sons to improve their performance. However, many people, including Dr Frank Jobe, the doctor who invented the method, believe any supposed post-surgical increase in performance is generally due to two factors.

The first is the athletes' increased attention to conditioning. The second is that it may take several years for the UCL to degrade in many cases. Over these years, the athlete's velocity will gradually decrease. As a result, the procedure likely allows the athlete to throw at the previous velocity before the start of the UCL to degrade. (Keri 2007)[6]

Rehabilitation

The time required for UCL rehabilitation often involves a year to eighteen months. This is a long process for athletes who desire to get back to participating at the same level as before the surgery. Rehabilitation involves a variety of exercises and modalities to assist the new ligament in regaining the strength it had before the surgeries.

The rehab for "UCL" or Tommy John Surgery is a very intensive and frustrating process, as mentioned in the USA Today article titled "Pitchers find patience hardest part of Tommy John surgery." [7]

Below is a sample rehab schedule for UCL surgery:

- Week One - the elbow is immobilised at a 90-degree angle in a splint or a brace. The patient may begin to move the hand lightly and begin gripping exercises.

- Week Two - a brace that will allow slight movement is worn, but the patient can start to perform each day's movement with the elbow, such as using the arm to eat. The elbow extension gradually increases, and the brace may be eliminated after four to six weeks.

- Weeks Three to Eight - The range of motion becomes very important. For the damaged region of the body to heal correctly, the shoulder and elbow must coincide in the process of healing. It is when many athletes begin to participate in sports.

- Week Ten - the athlete may start to simulate a throwing motion with a medicine ball, performing two-hand overhead lobs and chest passes.

- Weeks Twelve to Fourteen - many patients move from the two-handed throw to a one-handed throwing motion utilizing a 1-pound medicine ball. This type of therapy will allow the athlete to regain muscle memory. This function becomes engraved over time and is also known as an Engram.

- Weeks Fifteen to Sixteen - a throwing program may be started during this time. The athlete will begin on flat ground around 45 feet and softly throw; the athlete will do about 25 tosses, take a break, and then 25 more. Throwing will be performed every other day, and after two or three workouts, the athlete will move back in distance.

- Months Four to Five - this stage of therapy will include an underhand throwing motion in a very light manner.

- Month Six - at this level, athletes may start to throw at about 50% of their top speed. As mentioned in week 16, gradually increase the intensity, throwing with more force.

- Months Seven to Ten - athletes may participate in competitive situations.

- Months Eleven to Twelve - Athletes can return to full competition at close to 100% intensity. Still, it usually takes most athletes one full year of rehab to return to pre-surgery effectiveness.

Conclusions

With the 12-18 months of recovery, the rehabilitation process is the protocol required if athletes plan to return to participating and performing at their prior level. Athletes must utilize self-discipline while participating in the rehabilitation program and know when the time is right to increase the intensity of the therapy.

References

- PURCELL, D.B. et al. (2007). Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res, 455, p. 72-77

- FLEISIG, G.S. (1994). The biomechanics of baseball pitching, in Biomechanical Engineering. University of Alabama: Birmingham. p. 163

- LYMAN, S. et al. (2002). Effect of pitch type, pitch count, and pitching mechanics on risk of elbow and shoulder pain in youth baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med, 30 (4), p. 463-468

- WHITELEY, R. (2007). Baseball throwing mechanics as they relate to pathology and performance - a review. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 6 (1), p. 1-20

- LYMAN, S. et al. (2001). Longitudinal study of elbow and shoulder pain in youth baseball pitchers. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 33 (11), p. 1803-1810

- KERI, J. (2007). Interview With Dr Frank Jobe. [WWW] Available from: ESPN.com. [Accessed 13/10/2008]

- UNKNOWN (2004). Pitchers find patience the hardest part of Tommy John surgery. USA Today Sports Section, March 5, 2004

Page Reference

If you quote information from this page in your work, then the reference for this page is:

- McDANIEL, L. et al. (2009) Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction [WWW] Available from: https://www.brianmac.co.uk/articles/article045.htm [Accessed

About the Authors

Dr. Larry McDaniel is an associate professor and advisor for the Exercise Science program at Dakota State University, Madison, SD, USA. He is a former All-American football player and Hall of Fame athlete and coach.

Jason Kramp is an outstanding baseball pitcher and a student enrolled in Exercise Science at Dakota State University.

Nick Kruse is a student enrolled in Exercise Science at Dakota State and a veteran of the Iraq Conflict.