Menstrual Cycle

A female athlete's performance may depend on her menstrual cycle phase. The menstrual phase is the periodic discharge of 25 to 65ml of blood, tissue fluid, etc., lasting approximately 3 to 7 days. It comprises three phases: the menstrual phase (menses), preovulatory, and postovulatory. The menstrual cycle ranges from 24 to 35 days.

Example of the phases of a 28-day menstrual cycle:

| Days 1 to 5 | Days 6 to 13 | Day 14 | Days 15 to 28 |

| Menstruation phase | Pre-ovulatory phase | Ovulation | Post-ovulatory phase |

The effect of sport

Physically active women increase their chances of changes in their menstrual cycle. These include irregular cycles (oligomenorrhea) or complete cessation of the cycle (amenorrhea). In the general population, amenorrhea occurs in 2 to 5% of women of reproductive age, whereas women participating in sports can be as high as 40%.

Other factors

All women must be aware that exercise is not the only factor resulting in oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea. The other factors are a high stress level, body weight and body composition (% body fat level below 20%).

Athletes are prime candidates for oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea as they are likely to experience:

- Heavy training loads.

- High stress levels from trying to manage the training program with work and family life and the pressures of competition.

- As a result of the training, body weight may be reduced, and the fat level may fall below 20% for some months.

Consequences

Amenorrhea reduces the body's capacity to absorb calcium, decreases bone density and increases the risk of musculoskeletal injury in vigorous exercise.

Impact on training

For athletes experiencing a menstrual cycle, the most challenging time to race efficiently is during the week before menstruation and the week after ovulation(Williams 1997)[1]. At these times, increased levels of progesterone stimulate the brain's respiratory centre increasing ventilation rates (progesterone is also linked to mood swings). Athletes use breathing rate as an indicator of exercise intensity, so exercise can tend to feel harder at these times.

The maximum efficiency for athletes experiencing a 28-day menstrual cycle might be pre-ovulation (days 9 to 12) or post-ovulation (days 17 to 20).

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Laxity

The research results by Heitz (1999)[2] demonstrate that female ACL laxity significantly increases in conjunction with surging levels of estrogen and progesterone during the normal menstrual cycle.

Research by Slauterbeck (2002)[3] found a significantly higher number of ACL injuries occurred on days 1 and 2 of the menstrual cycle.

Female athletes may need to take precautions to reduce the likelihood of ACL injury. A systematic review by Belanger (2013)[4] of 13 clinical trials investigating the effect of the menstrual cycle on ACL laxity found that there is evidence to support the hypothesis that the ACL changes throughout the menstrual cycle, with it becoming laxer during the pre-ovulatory (luteal) phase. Overall, these reviews found statistically significant differences for variation in ACL laxity and injury throughout the menstrual cycle, especially during the pre-ovulatory phase.

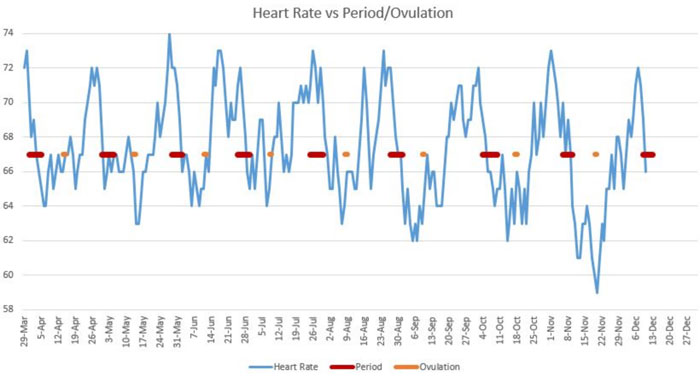

Impact on Resting Heart Rate

Research indicates that the menstrual cycle impacts an individual's resting heart rate. Moran (2000)[5] and her team found that resting heart rates (RHRs) show distinct values for the four phases of the menstrual cycle. RHR was significantly higher in both the ovulatory and luteal phases (the second part of the cycle) compared to menstruation and the follicular phase (the first part of the cycle). Shiliah (2017)[6] and her team found that during a woman's fertile window, the period of about six days when a woman can become pregnant, her resting heart rate increases by about two beats per minute, on average, compared with her heart rate during menstruation.

The following graph is an example of an individual's resting heart rate, periods and ovulation for nine months:

References

- WILLIAMS. T. (1997) Menstrual Cycle Phase and Running Economy. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 29(12), p. 1609-1618

- HEITZ, N. A. et al. (1999) Hormonal changes throughout the menstrual cycle and increased anterior cruciate ligament laxity in females. Journal of Athletic training, 34 (2), p. 144

- SLAUTERBECK, J. R. et al. (2002) The menstrual cycle, sex hormones, and anterior cruciate ligament injury. Journal of athletic training, 37 (3), p. 275

- BELANGER, L. Burt, D. et al. (2013) Anterior cruciate ligament laxity related to the menstrual cycle: an updated systematic review of the literature. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 57 (1), p. 76.

- MORAN, V. H. et al. (2000), Cardiovascular functioning during the menstrual cycle. Clinical Physiology, 20, p. 496-504

- SHILAIH, M. et al. (2017) Pulse Rate Measurement During Sleep Using Wearable Sensors, and its Correlation with the Menstrual Cycle Phases, A Prospective Observational Study, Scientific Reports, Volume 7, Article number: 1294

Page Reference

If you quote information from this page in your work, then the reference for this page is:

- MACKENZIE, B. (2007) Menstrual Cycle [WWW] Available from: https://www.brianmac.co.uk/menstrual.htm [Accessed